In a perfect world, world leaders attending the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD), which is starting next week in Seville, would be committing resources in a room filled with 272 million children, adolescents and youth to get them back to school.

A couple of years ago, we showed that modest changes in high-income countries’ official development assistance could make a difference. One of the four we highlighted was for this spending to increase by 0.4 percentage points (from 0.3% to 0.7%) of their gross national income. This would help reduce low- and lower-middle-income countries’ total financing gap to get these children to school by one third.

Yet the world is far from perfect. And the only commitment rich countries have just made this week in The Hague was to increase the amount they spend on weapons by 2.4 percentage points (from 2.6% to 5%) of their gross domestic product (GDP). The entire annual amount of aid to education is equivalent to just two and a half days’ worth of military spending.

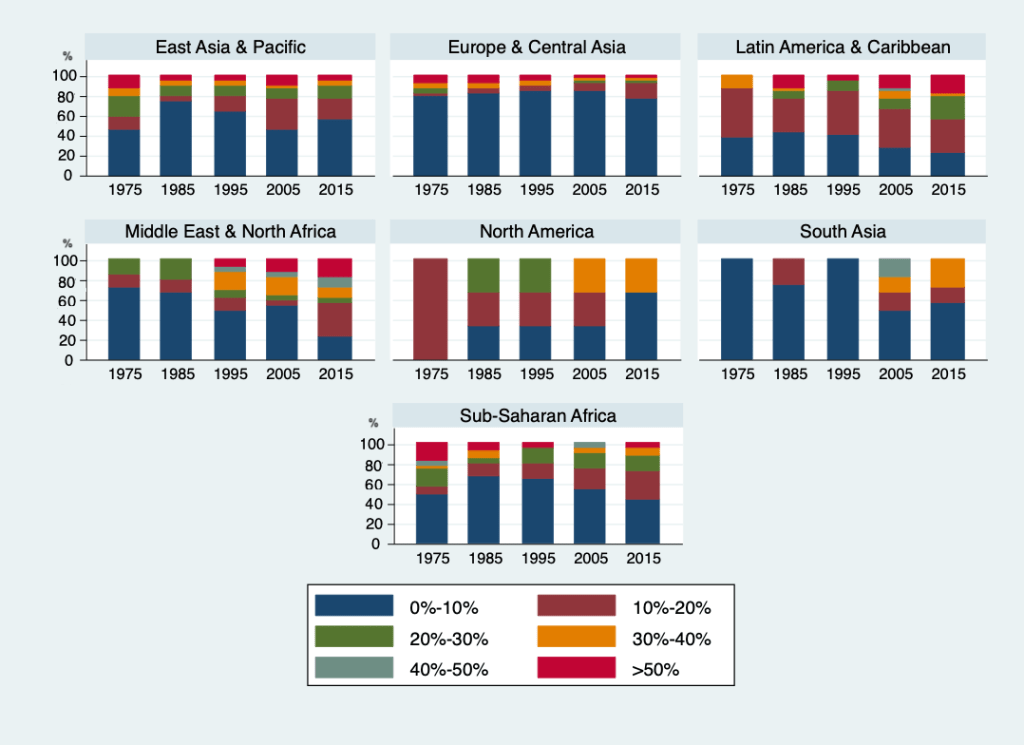

Today a new paper we publish shows that not only are donor countries not increasing official development assistance by 0.4 percentage points, to fulfil a commitment they have been failing to meet since 1970, but they are on course to decrease aid by 0.1 percentage point, a fall as rapid as the one last observed in the 1990s.

Aid to education is in fact projected to fall by a quarter between 2023 and 2027, which is almost twice as much as we estimated just a few weeks ago.

What is new?

The blog we published in April contained all announcements that a select group of high-income European countries and, especially, the United States had made in early 2025. There is no news in that respect. But the new piece of information presented in the paper is that there are now clear signs that aid to education had already fallen by 12% in 2024 before even the new budget announcements had been made.

This is based on the first-ever analysis of the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) database, a standard that was introduced in the late 2000s but whose use has expanded. While it has considerable disadvantages relative to the standard data published by the OECD, there is sufficient evidence that it matches the long-erm trends of donors accounting for at least half of total aid to education.

Global education aid is projected to fall by one quarter

Why is that important?

There has been a growing sense that aid has been losing in importance. It is true that grants, of which aid is a major component, have declined rapidly as a share of low- and lower-middle-income countries’ GDP in recent years. For a group of 31 countries in Africa, Asia and the Pacific, grants fell from 3.5% to 2% of GDP (and the median share even more, from 3.3% to 0.9% of GDP). For example, grants as a share of GDP fell from 1.7% to 0.2% in Ghana (-88%), from 6.4% to 0.9% in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (-86%), from 5.8% to 1.3% in Malawi (-78%), from 3.5% to 0.4% in Mali (-89%) and from 6.8% to 0.8% in Vanuatu (-88%).

Yet the volume of aid is still sizeable in low-income countries and equivalent to 12% of their total education spending, or 17% if household spending is excluded.

Debt calls for more, not less support

Aid is also important in a context where public budgets are under pressure. Globally, public education expenditure has fallen by 0.4 percentage points as share of GDP and by 0.7 percentage points ass share of total public expenditure since 2015. The falls are larger in middle-income countries, which are more exposed to the growing public debt.

While countries are not yet in the situation they faced in the 1980s and 1990s, when they lost two decades of education development as a result of structural adjustment programmes, the same point could be reached in a few years if trends continue and no mitigating measures are taken.

The upcoming conference in Seville is calling for a new development-oriented debt architecture. If the previous debt crisis left one lesson, it was the need to not let the debt crisis fester. Procrastination and poor choices of international financing institutions inflicted unnecessary pain on social development.

Will the International Conference on Financing for Development change aid policies?

The role of aid as a pillar of international cooperation is under threat, alongside other pillars of multilateralism. The question is whether shrinking aid budgets will force tough but overdue choices so that aid can serve national development objectives much better than in the past.

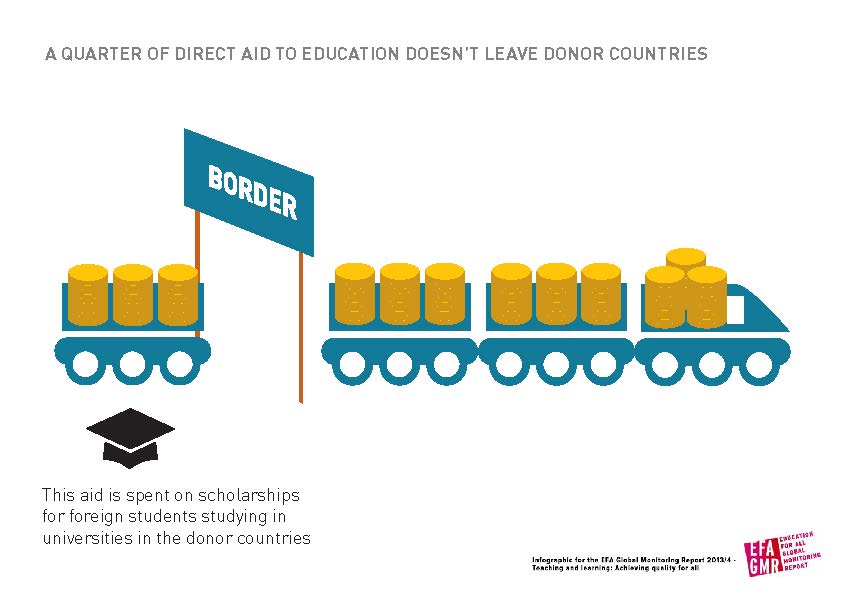

Aid has been increasingly delivered in ways that bypass national systems, especially by bilateral donors who channel only 17% of aid through recipient governments, compared to 60% by multilateral donors. As aid to education is projected to decline, the paper recommends shifting more resources:

- Through multilateral channels, while ensuring less earmarking of aid

- Through national budgets, in order to reverse the trend towards project-based aid

- Toward system strengthening, in order to build institutions instead of achieving short-term results

- Toward lowering the cost of borrowing, while building a new development-oriented debt architecture

- Toward global public goods in education, which are most at risk in a time of aid cuts

Join us in amplifying the messages from the papers by showing this presentation to your networks, by sharing these social media resources and downloading the reports.