Education technology is often seen as a solution for increased access to education and improved learning outcomes as explored in the 2023 GEM Report. Technology makes it easier to create and share educational resources. But when the content is not available in learners’ languages and not adapted to context, linguistic and cultural barriers emerge that widen inequalities.

Language is an integral part of identity. Learning is enhanced when language identities are recognized. Simply put, students perform better when concepts are explained in terms of their personal context and experience. Although some teachers adapt and create materials for local contexts, this can take time and is not easily achievable with existing digital materials.

Take the Pacific as an example, where nearly 25% of the approximately 6,000 distinct languages in the world are spoken. Papua New Guinea is the most linguistically diverse country in the world, with over 800 indigenous languages spoken. Making education resources available in a context of such diversity, whether digital or not, is an insurmountable challenge.

The prevalence of English-speaking materials threatens local languages and encourages students to master the global language rather than their own. The use of languages other than those spoken at home reflects how education is dominated by certain groups also through content creation. As early as 2005, online forums in Niue were mostly comprised of posts in English or using some English. In Samoa, where there is only one spoken indigenous language, most online content is in English.

This leads to calls for open educational resources to be available in local languages. In Kiribati, the Ministry of Education, with support from UNICEF, developed high-quality video lessons and quizzes in English and Gilbertese, the local language. The resources are hosted on the Learning Passport platform and accessible to all. To promote the local language, Samoa also has a rich library of resources in Samoan accessible through the Samoan Digital Library.

Cultural relevance is a cornerstone of sustainable education. Digitizing traditional knowledge, developing curricula in local languages, and aligning technology with Indigenous values are essential steps. In the Solomon Islands, culturally relevant educational resources have been created, digitized and published online for public access, for instance. Although only available in English, primary school-level supplementary reading materials also feature local stories such as ‘Under the Ngali Nut Tree’ and ‘Mautikitiki and the Giant Coconut Crab’.

When done right, rather than digitization threatening local languages and cultures, it is possible for it to be used to preserve and promote them. The preservation of Tokelau’s language and culture is the first priority highlighted in the 2020–2025 Tokelau Education Strategic Plan, for example. It seeks to increase culturally appropriate print and digital resources for language and content learning, including Tokelau language e-books at various levels with embedded audio for online literacy-focused learning. Additionally, the plan calls for the creation of a Tokelau language website with publicly available resources.

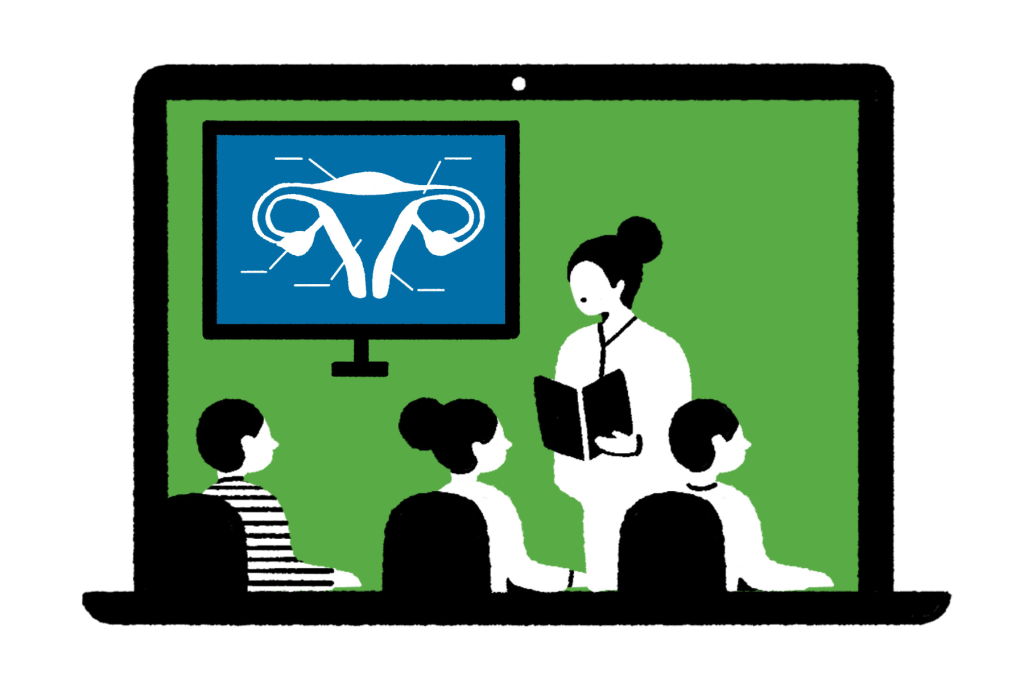

One illustrative example of what cultural relevance can look like in the digitalization of society is in the form of story telling. Catalpa, an organisation that works with indigenous practices of telling stories and interacting in talanoa, a word derived from Fijian and Samoan languages meaning ‘talk’, in order to bring together teams to share knowledge and discuss ways teachers could be supported. Co-developed with 8 Pacific science fellows appointed by education ministries, Catalpa’s Pacific eLearning Programme provides 100 science activities, 34 job-embedded professional development activities and 22 micro-courses for teachers in the Cook Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. Contextualized and relevant content was produced for science teachers, including lessons on mangroves, ocean and land, reef ecosystems, how canoes float, and the theory behind the fermentation of some local foods.

Similar ideas have been used in Australia to facilitate culturally relevant storytelling, promote engagement and improve learning for students from Aboriginal communities. Multimedia platforms, such as Digital Creative Storytelling, document Indigenous stories in collaboration with elders from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Culturally responsive digital games have increased the engagement and motivation of primary school students from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds.

Similar examples and efforts are also found in other corners in the world, from special radio strategies for indigenous students in Mexico, to a large multilingual story platform in India with over 323 languages . As the pace of digital transformation increases, this nexus of culture and education is particularly important. From language to content and now to the shape of artificial intelligence algorithms, there are multiple different hot spots requiring attention to ensure that the use of technology in education is appropriate.