Digital technology is reshaping education. Without education leaders steering such changes with the interests of students and teachers in mind, technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), there are real risks ahead.

The promise and the peril

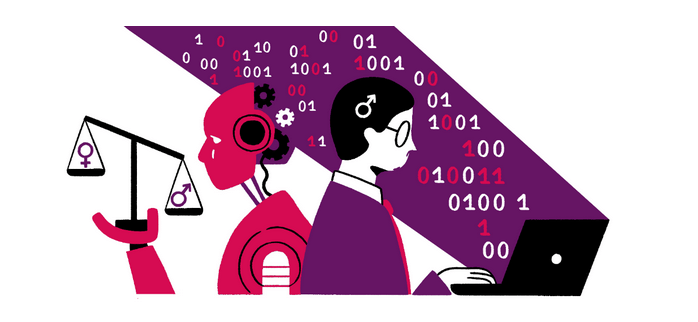

AI can personalize learning, support students with disabilities and ease the administrative burden on teachers. But without leadership at the helm, these opportunities risk being overshadowed by serious concerns: privacy violations, algorithmic biases and growing inequality.

For example, AI opens unchartered territory of harassment through deep fakes, especially images, which is spilling over into school environments. For instance, schoolgirls and female teachers have been victims of deepfake pornographic images circulating in schools.

Machine learning algorithms are used to make decisions that can have a major impact on people’s lives. Far from being fair and objective, algorithms carry the biases of their developers and can reproduce or deepen inequality. The gender edition of the 2023 GEM Report, Technology on her terms, showed how algorithms at play in social media impact girls’ well-being and self-esteem, exacerbating negative gender norms or stereotypes.

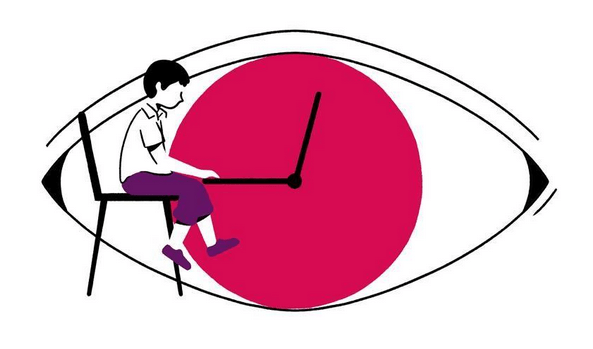

Facial recognition systems also raise concerns about privacy. In Brazil, facial recognition has been used to monitor access to public services, including schools, with the aim to monitor student attendance. However, the programmes collect other information and can monitor and record information on excluded and marginalized groups at the expense of their privacy. As a recently approved law for data protection does not cover data processing for public security purposes, these systems could be used to profile and punish already vulnerable groups. In China, privacy concerns over the collection of data on students’ classroom behaviour with cameras have driven initiatives to ensure their use remains in check. In the US state of Texas, where new rules have changed access to public education for undocumented immigrants, at least eight school districts use facial recognition that is also used for law enforcement purposes.

Digital tools without safeguards are not a solution; they can become a trap. Education leaders must set the rules of the game, ensuring that AI enhances rather than replaces teaching. Yet, a 2023 UNESCO survey found that publishing a new textbook requires more authorizations than the use of Generative AI tools in the classroom.

Equity before innovation

Policies must be anchored in equity, well-being and quality, never in technology for technology’s sake. China has guidelines for the use of AI in schools to ensure the safe and compliant use of data and the protection of the rights and interests of teachers and students. Japan has guidelines for the use of AI, updated in 2024, which define the appropriate use of generative AI in education and highlight potential risks for personal information, privacy and copyright.

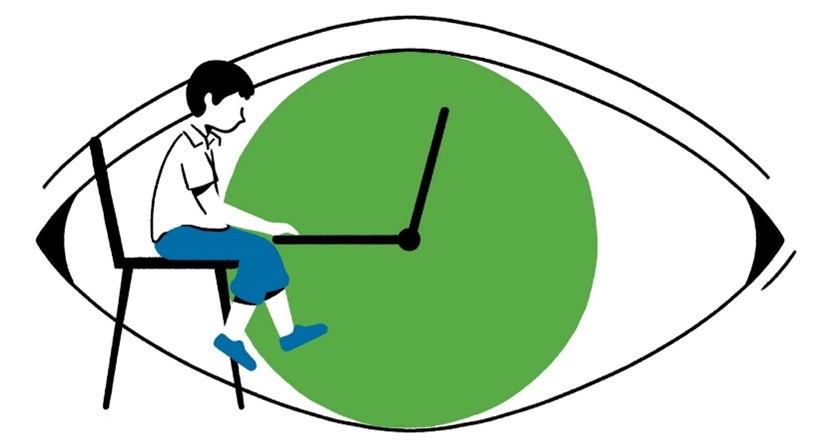

Policies on AI in education must be human-centred, as emphasized in the UNESCO Guidance for generative AI in education and research, which included a recommendation for AI tools not to be used before the age of 13 years in the classroom, and for teacher training – which should also be extended to school leaders.

Technology that excludes is not progress. If we were to apply the principle of ‘do no harm’ to the use of AI, whereby no plan or programme can be put in place if it risks actively harming anyone at all, it would fall at the first hurdle. One in four of the world’s primary schools lack electricity. Only 40% of primary, 50% of lower secondary and 65% of upper secondary schools are connected to the internet.

But the market for AI in education is growing apace. It is expected to grow from $5 billion in 2024 to $112 billion by 2034, if one believes those who try to promote it in order to put pressure on ministries of education to ‘keep-up’ with the change. But then the implications for scant resources for teacher salaries and classroom facilities have to be considered. Even basic digital transformation already risks widening the financing gap by 50% in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Adding AI on top would be inadvisable, unless we want technology to be the only priority in education. Connectivity, infrastructure, and targeted support must come first—turning technology into a tool that narrows divides instead of widening them.

Collaboration for sustainable change

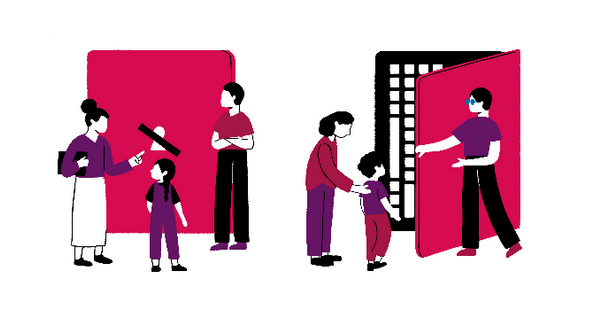

No education leader can navigate this shift alone. “When principals talk to teachers about technology, there’s an idea of ‘You must do this’, a handing down of orders. I don’t know any adult who responds well to this”, said a teacher surveyed for the 2023 GEM Report

In order to help teachers capitalize on the benefits of technology, school leaders need to be instructional leaders who understand the instructional imperatives of teaching well with technology. That way they can support and champion technology as a vehicle to improve instruction and deepen student learning. Only when leaders share lessons, build networks and bring teachers into the process, does AI have a chance to become a driver of sustainable improvement – and not disruption for disruption’s sake.

Leaders with a compass

To make schools better and not just more technology-enabled, leaders need digital literacy, ethical judgment and the ability to guide schools through change. This will be a significant priority for most countries if the speed of AI in education is to continue at its current pace.

Our Latin America regional report, Lead for democracy, found that, in 10 of the 17 countries principals were not required to demonstrate any ICT skills and/or knowledge for their post. In the Republic of Korea, the decision to introduce AI textbooks into schools by March this year was resisted by the Nationwide Superintendents’ Association who said there was not enough time allocated to train schools for the change.

Identifying training needs within schools is up to principals, but assisting schools with training options requires strong system leaders too. In the Republic of Korea, Regional Project Support Teams bring together local education offices and teacher training institutions to conduct pilot projects to strengthen teachers’ AI and digital capabilities.

And they cannot do it alone. ICT coordinators must be part of the team, maintaining systems and solving technical issues, to help leaders and teachers focus on what matters most: teaching and learning.

Innovation without oversight risks that children become collateral damage. Trialling AI recklessly in schools could widen existing gaps instead of opening doors. The choice lies with education leaders. With vision, training, and support, they can ensure AI strengthens, not weakens, learning for every child.