Calls for debt relief for poor countries, for example from UNDP and Oxfam, have been pointing at an obvious question. How can we ask countries to invest in education when they are fighting for fiscal survival?

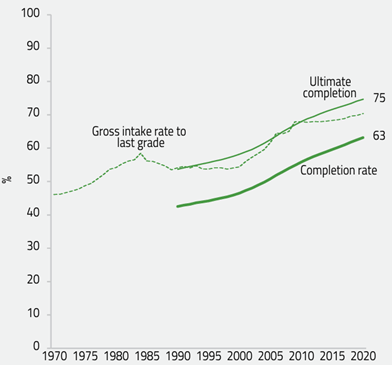

After all, during the previous debt crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, education and other social sectors were dramatically affected. Primary completion rates in Africa did not recover their 1984 levels for another 20 years due to public expenditure cuts that were part of structural adjustment programmes.

Selected measures of primary completion, sub-Saharan Africa, 1970–2020

Source: World Bank WDI (gross intake rate) and VIEW website (completion rates)

This fear explains why debt relief and innovative mechanisms for reducing debt servicing are high on the agenda at the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development taking place at the end of this month.

A range of factors had increased the vulnerability of many countries, which was exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which called for increased public spending. The share of lower income countries in debt distress or at high risk of falling into it increased from 21% in 2013 to 59% in 2021. While it fell to 53% in 2024, it means that more than half of countries are still in that difficult position.

In the 78 countries eligible for International Development Association concessional loans, interest payments on debt have quadrupled in a decade, reaching USD 35 billion in 2023. More than one third of their external debt involves variable interest rates that could rise suddenly. In 2020–22, there were 18 sovereign defaults across 10 countries, more than at any time over the past two decades. Meanwhile, high debt burdens are constraining the ability of these countries to borrow. New external loan commitments dropped by 23% to USD 371 billion in 2022, and new loans have become more expensive and less accessible.

Source: IMF Economic Outlook (2023) (2009–14) and IMF Independent Evaluation Office (2025) (2015–22).

The impact of debt on education

Debt has outpaced income growth in low- and lower-middle-income countries. As shown in the 2024 Education Finance Watch, the gross national income (GNI) in low-income countries rose on average by 33% between 2012 and 2022, while the combined external debt stock rose by 109%. In lower-middle-income countries, the GNI rose on average by 21% while the combined external debt stock rose by 46%.

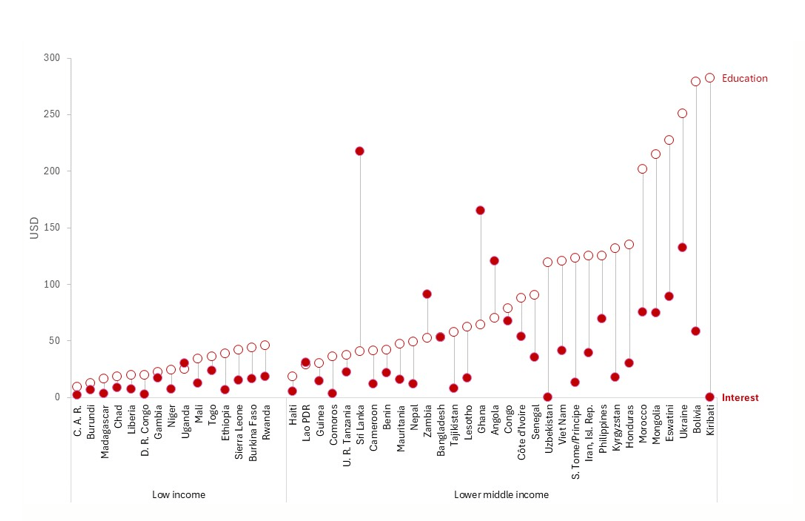

Debt constrains countries’ ability to fund education. Interest payments outpace education expenditure in many countries. Rising interest payments have coincided with a decline in the share of government budgets allocated to education in countries like Ghana and Zambia. Interest payments are equivalent to 43% of education spending per capita in low-income countries and 48% of education spending per capita in lower-middle-income countries.

Yet external borrowing can be critical for education financing, particularly in countries whose domestic resources may be insufficient. Borrowing for education can be a sound investment if it leads to improved economic outcomes by producing a more educated population, which increases productivity and earnings, which in turn can help the country to repay its debt.

Interest payments have outpaced education spending growth in many countries

Source: Author estimation using EFW2024 database and UNCTAD data.

Learning from our mistakes. What does the 1980s debt crisis teach us?

In the 1980s, debt to official creditors was rescheduled but arrears accumulated: structural adjustment packages reduced public service employment, eliminated food subsidies and cut social expenditure. For every 1% increase in external debt-to-exports, there was a 0.33% fall in public education expenditure; public spending on education was highly volatile, and more volatile than health spending.

In 1996, the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative led to complete debt relief of USD 59 billion. This was extended through the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative in 2005; countries developed poverty reduction strategy papers, introduced social sector policy reforms and increased social expenditure. Debt relief helped countries get their education development trajectory back on track.

Compared to the 1980s debt crisis, today’s crisis is not yet as severe. During the peak of the previous debt crisis in 1994, the median country’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 72% while it was only 33% at the end of 2021. Debt-to-export ratio was 318% in 1994 but 137% in 2021. At current trends, though, there may be a return to 1990s’ debt ratios by 2030.

Moreover, the two crises differ significantly in the composition of the debt. The share of domestic debt in total debt, which was less than 20% in the mid-1990s, had grown to 35% by 2021. There was a lower risk to exchange rate depreciation but a bigger risk of systemic crisis.

Also, external debt is more diversified, which affects the scope of potential solutions. Official creditors (Paris Club) accounted for 39% of total debt in the mid-1990s, which was mainly in concessional terms. But their share fell further from 28% in 2006 to 10% in 2020, while the share of China and non-Paris Club creditors increased from 8% to 22% and that of commercial creditors from 10% to 19%. These borrowing agreements sometimes lacks explicit information on the exposure of indebted countries to risks.

Finding solutions

Some recent developments aimed to reduce the load, such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative triggered by COVID-19 and the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatment in 2020. The latter struggled with implementation, with only Chad succeeding in requesting debt treatment. Some countries have carved out solutions, with Ghana reaching a USD 3 billion agreement with the IMF after defaulting in 2022, and Zambia arranging a three-year grace period on interest payments after defaulting in 2020.

Solutions include debt restructuring, debt relief, debt swaps and debt-for-development. Effectively applied, they can alleviate immediate financial pressure, allowing resources to be redirected toward education and other social spending. But they can be complex and time-consuming. For example, debt restructuring may not lead to long-term fiscal stability.

Debt swaps forgive or reduce a portion of the debt in exchange for a commitment to invest. However, they need to meet criteria, considering the initial debt position and the swap’s likely effects on debt sustainability; the net financial gains for the debtor; debt management capacity and commitment to transparency; and finally the opportunity costs for debtor and donor.

Good candidates for debt swaps have a sustainable long-term debt outlook but are experiencing temporary liquidity pressures. This is usually in smaller economies, where swaps can smoothen debt repayment profiles and improve liability management. It is also important to ensure that spending commitments are aligned with development goals and strategies. And these financing mechanisms must be complemented by other actions: domestic resource mobilization, efficient spending, effective public financial management and more.

The recently released draft outcome document of the Financing for Development conference in Seville calls for a new intergovernmental process on sovereign debt to bring the voices of developing countries into international norm setting on debt. And it recommends ‘setting up a new debt facility to work on scaling up debt swaps and other tools to help countries that need more fiscal space’. We hope this blog explains why that is important.